There’s something I’ve been thinking a lot about, but struggling to find the words to explain: the connection between travel and street art. I’ve had fumbling conversations in which I attempt to articulate it, flapping my lips like hands gasping at butterflies, trying to gather vague supports for an unformed thesis. An idea has been forming in me, very far inside my brain, amid the murmuring currents of subconsciousness—like a toddler without the vocabulary to express herself, feeling emotions she doesn’t understand, but only knows are true.

There’s something I’ve been thinking a lot about, but struggling to find the words to explain: the connection between travel and street art. I’ve had fumbling conversations in which I attempt to articulate it, flapping my lips like hands gasping at butterflies, trying to gather vague supports for an unformed thesis. An idea has been forming in me, very far inside my brain, amid the murmuring currents of subconsciousness—like a toddler without the vocabulary to express herself, feeling emotions she doesn’t understand, but only knows are true.

And then a friend posts a video on Facebook that starts to explain everything I’ve been thinking and struggling to say. Thank God.

Chile Estyle has released the first documentary in what I’m hoping will be an ongoing exploration of the evolution of the burgeoning and blossoming Chilean spin on the global phenomenon of street art. And in its coverage of the specifically Chilean take on the art form, Chile Estyle touches on what I’d felt street art is doing all over the world: revealing (like a striptease) just a little more of the soul of a place.

I’ve been hearing a lot about Chilean street art, most recently in a photo essay by Oakland artist Obi Kaufmann (discussed in connection to his recent mural here). We stood around The Oakbook’s small gallery space, and I listened to Obi talk about the distinctions of Chilean street art: materials lending a unique aesthetic (due to the relative absence of aerosol spray paint in the country), and the culture of muralism leading to the acceptance, even support, of the community (you’re more likely to see street art on the sides of businesses and schools than abandoned warehouses). I can’t say I saw a lot of street art when I was in Santiago, nearly five years ago. Something has changed.

Judging from the picture presented by Chile Estyle, the explosion of street art in Chile has a lot to do with the country regaining confidence and reestablishing its identity. Artists in the video talk about seeing work from New York, Europe, Brazil, and taking pride in the fact that Chile can contribute works just as valuable and important. But, of course, it comes with their own distinct style, a product of their own history and culture.

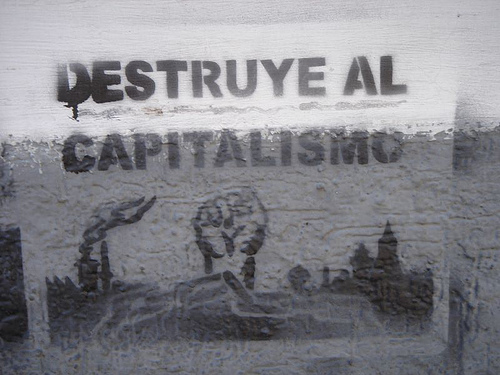

The video discusses “Chilean graffiti identity,” informed by the country’s tradition of political muralism. Uber populist and at its core revolutionary, graffiti and street art are seen as an extension of the self-expression that acted in rebuttal to (right-wing) major media outlets—“walls are taken much like a newspaper.” The tradition has lent a culture and community far more tolerant of street art than in most places of the world; it’s seen as “a gift for the people,” rather than vandalism. And, as Chilean street art has begun to garner international attention (like in a recent exhibition at LA’s Carmichael Gallery), it’s become a source of national pride.

How different this is from the culture of street art around the world. And more than just isolated vestiges of self-expression, one can take Chilean street art as a product of the country’s past and perhaps one of best reflections of its contemporary culture.

This is what I’ve been suspecting street art could do. In moments of blinding conviction, I’ve felt that street art, in its democratic and uncommercialized glory, can capture placeness just as well as food or architecture or music or any number of things people look to when they travel. In a continual cross-pollination of artists and influences, cities wear a bit more of their souls on their walls, as though the murals and stencils and wheatpastes were images from its dreams. It’s the way a city like Tel Aviv becomes a mecca for political street art, the way the aesthetic now known as Mission School bloomed in the alleyways of the 90’s SF Mission, whispering its stories in neon—and the way the tradition of political muralism paved the way and painted the walls for a purely Chilean approach to the art form.

And I still don’t have the words for it, the right or complete words to explain it all—because of course, virtually the same things could be said about all art forms, in how they inform and are informed by place. But something in me sparks when it comes to graffiti, in the same place of my brain that travel ignites. I guess the only thing to do is keep digging, poking, on the internet and down alleyways, until I stumble upon the thing it is I’m trying to say—painted on the walls in plain sight.

Recent Comments