Everything grey. Not the soft, floaty kind of grey, but heavy, brooding, impenetrable—like being underwater, like walking through a dream: the landscape all sand and crippled trees, windswept by something that came before you, something you can’t see, some kind of endless passing of which the fog is only a part, only a symptom of a larger sadness—the solitary transience of the Northern California coast.

Everything grey. Not the soft, floaty kind of grey, but heavy, brooding, impenetrable—like being underwater, like walking through a dream: the landscape all sand and crippled trees, windswept by something that came before you, something you can’t see, some kind of endless passing of which the fog is only a part, only a symptom of a larger sadness—the solitary transience of the Northern California coast.

Destination weddings are fun, because the party doesn’t stop, isn’t confined to six hours in impractical shoes and unforgiving fabrics. And you get to feel like you’ve gotten away, vacationed, traveled. So it’s a two-for. Guests complain about them because they’re more expensive, discreetly accusing hosts of choosing distant locales to limit the guest count. Which could all be well and true, but my first experience at a destination wedding pretty much ruled.

To qualify, it wasn’t much of a destination—a two-hour drive down the Monterey Peninsula to Asilomar, what could have easily been a day trip. But something about it gave me just a taste of travel, a hint, like passing someone smoking a cigarette on the street—not the real thing, but enough of a whiff to remind you of the real thing, evoke some sort of not-so-secret longing you try to muscle through, distract yourself from, most days. Something about the weekend was twinged with longing (for what?), some kind of sickly bittersweet lonely. Maybe it was the fog.

Asilomar is a state beach and rustic conference grounds billed as a “refuge by the sea.” It’s got some history, some charm, some Arts & Crafts style flair. But the conference grounds/hotel was unfortunately bought out by some large hospitality chain in recent months, and the service has gone from homey mom-and-pop to corporate nickel-and-dime-and-don’t-give-a-fuck-about-quality. Whatever. The scenery is still beautiful and the wedding was still awesome.

The weekend started with a Friday afternoon BBQ and wiffle ball tournament that got froze out by the cold. We retreated to the bridesmaid cottage (which was more like a suburban home than a cottage, beige carpeting and all) for epic hanging-outage.

The cool thing about the whole weekend-long aspect of the wedding was that it really gave you a chance to meet people. Not just superficially, but, you know, to bro down. I suppose the destination wedding thing could be hell if you were trapped in some resort with someone’s insane family, but my friends Katie and Steven have pretty awesome friends. They’re scattered around the Bay, LA and NYC; the disparate groups had never really had a chance to meld, so the wedding served as the ultimate meeting (the whole reasoning behind having it be a destination affair). I’ve got a particular affinity for rad, smart, independent girls, and got to meet quite a few of them.

I also got to hang out with some super good old friends, the kind of people that have seen you grow, that you’ve seen grow—who you’ve walked through all sorts of brutal life shit with. The beautiful part is that we’ve managed to come out on the other side, all limbs in tact. (I’ve also got an affinity for survivors.) There’s not so many of us, you know, when it comes right down to it. And getting to hang out with a couple dope old friends that you’ve been through some shit with definitely serves to renew faith, lend some perspective, validate some small feeling inside you that everything might just be okay—almost like a small kind of prayer.

I also got to hang out with some super good old friends, the kind of people that have seen you grow, that you’ve seen grow—who you’ve walked through all sorts of brutal life shit with. The beautiful part is that we’ve managed to come out on the other side, all limbs in tact. (I’ve also got an affinity for survivors.) There’s not so many of us, you know, when it comes right down to it. And getting to hang out with a couple dope old friends that you’ve been through some shit with definitely serves to renew faith, lend some perspective, validate some small feeling inside you that everything might just be okay—almost like a small kind of prayer.

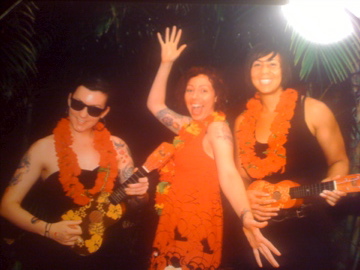

And then there was the dance party.

I like to get down; who doesn’t? But there was something different about this dance party. It wasn’t just the killer music (soul, 80s, old rock ‘n roll), and it wasn’t just the super cool folks. It was fueled by something within, some drive to… escape? That’s not exactly right, but close—a drive to push through a kind of pain, not just an immediate circumstantial sadness (checking the phone for text messages), but the deeper, desperate lonely beneath that (gone, gone, and left me here).

Whatever it was, I let loose like I rarely do, like I was trying to dance my way out of something. I thought of the kids that used to hang out the swimming pool I worked at as a teenager. It was North Oakland, an inner-city environment to say the least, filled with a bunch of little hood rats with nothing better to do than hang around the pool all day. Forget what they say about kids having no worries—a lot of these kids had pretty gnarly home lives. But I used to watch the way they’d play and find some sort of solace in it—the particularly child-like ability to shed all that shit and just play, find some small moment of release amidst the dysfunction and poverty and pain. Almost like a small kind of prayer.

Whatever it was, I let loose like I rarely do, like I was trying to dance my way out of something. I thought of the kids that used to hang out the swimming pool I worked at as a teenager. It was North Oakland, an inner-city environment to say the least, filled with a bunch of little hood rats with nothing better to do than hang around the pool all day. Forget what they say about kids having no worries—a lot of these kids had pretty gnarly home lives. But I used to watch the way they’d play and find some sort of solace in it—the particularly child-like ability to shed all that shit and just play, find some small moment of release amidst the dysfunction and poverty and pain. Almost like a small kind of prayer.

Let’s just say at the end of the night, it was me, a dude who looked like Owen Wilson in Zoolander and danced like a gay stripper, and a ten year old girl who could break dance. Magical.

The next morning was all eggs and syrup and sleeping in. There’d been an after-party, then an after-after-party, and everyone was spent. We staggered around in the dream-like fog, hair half-curled and wearing sweatpants. People bundled up on the beach and ate the remainders of potato salad and cupcakes, wrapped in blankets and sleepiness and the grey, grey sky of California.

Recent Comments